The year 1969 stands as a pivotal moment in the history of the American Civil Rights Movement. It was a time of significant transition, marked by both progress and profound challenges. The movement, which had gained momentum in the previous decade, faced new dynamics as it navigated the complex social, political, and cultural landscape of the late 1960s.

Setting the Stage: The Social Climate of 1969

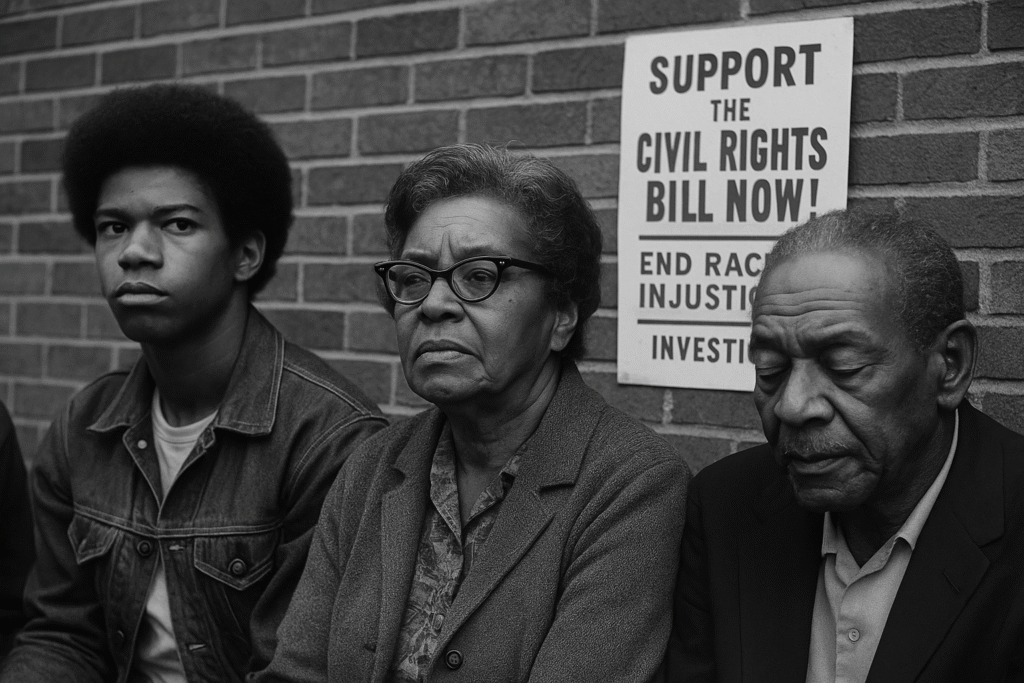

By 1969, the United States stood at a crossroads of monumental social change. The optimism generated by landmark legislation earlier in the decade—particularly the Civil Rights Act of 1964—had begun to give way to a more sobering reality. Although the Act had formally outlawed segregation in public spaces and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, its implementation was slow and uneven across the country. Many African American communities continued to endure deep-rooted systemic inequalities. Substandard housing, underfunded schools, limited job opportunities, and poor access to quality healthcare remained part of daily life in cities and rural areas alike.

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968 marked a seismic shift in the movement. As the most prominent voice for civil rights, King had embodied a philosophy of nonviolent resistance coupled with a moral call for economic justice and racial equality. His death left a void in leadership and direction, creating a moment of reckoning for the broader civil rights community. Some activists called for continuing King’s strategy of peaceful protest, while others, disillusioned by slow progress, gravitated toward more militant approaches.

The media played a dual role during this period—serving both as a spotlight and a magnifying glass. Televised coverage of civil rights protests, clashes with police, and the ongoing Vietnam War brought raw, unfiltered images into American living rooms. Scenes of peaceful demonstrators being met with violence not only mobilized new supporters across racial lines but also ignited fear and resistance in conservative circles. The media’s influence shaped public perception profoundly, turning the Civil Rights Movement into a national—and often polarizing—conversation. By the end of the decade, this dynamic tension had set the stage for new voices, strategies, and battles for justice in the years ahead.

Key Events and Milestones of 1969

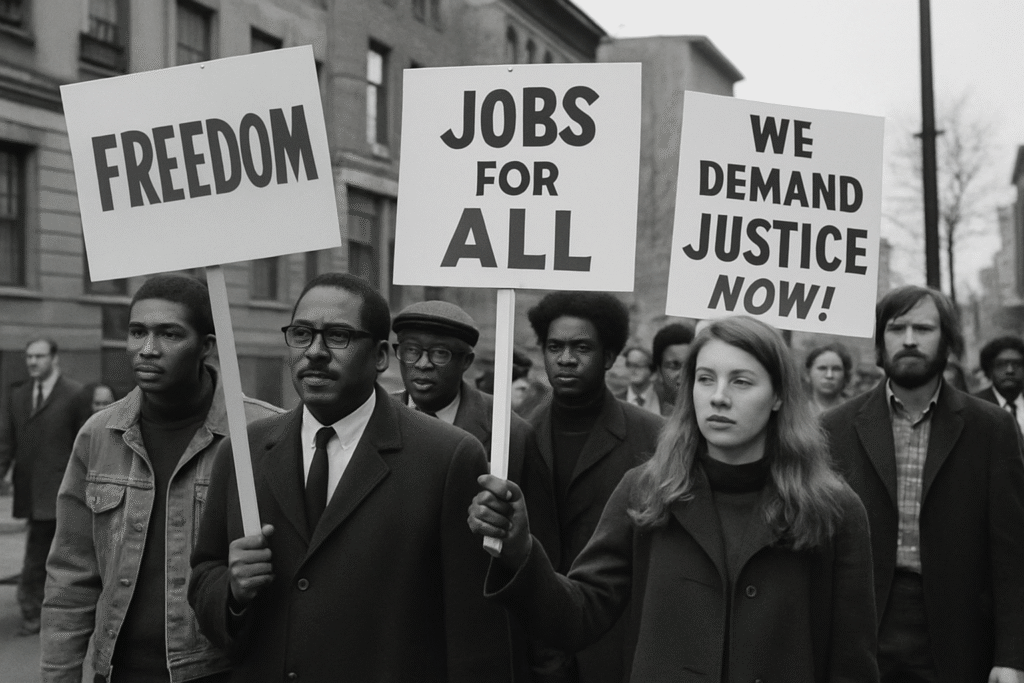

The year 1969 was a pivotal one for the Civil Rights Movement—marked by profound determination, yet increasingly fractured strategies and mixed outcomes. Activists and organizations worked tirelessly to confront not only racial discrimination but the underlying economic inequalities that disproportionately affected marginalized communities.

Among the most ambitious initiatives was the continuation of the Poor People’s Campaign, a movement launched by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. before his assassination in 1968 and carried forward by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) under the leadership of Ralph Abernathy. The campaign sought to expand the civil rights struggle to encompass economic justice for all poor Americans, regardless of race. In the spring of 1969, protesters established “Resurrection City”—a makeshift encampment on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.—as a physical symbol of their demand for an “economic bill of rights.” The site drew attention to issues such as housing, employment, and hunger. However, logistical difficulties, poor weather, and limited governmental response plagued the effort. Without King’s unifying presence and amid increasing political fatigue, Resurrection City was ultimately dismantled after six weeks, leaving a legacy of both hope and unfulfilled ambition.

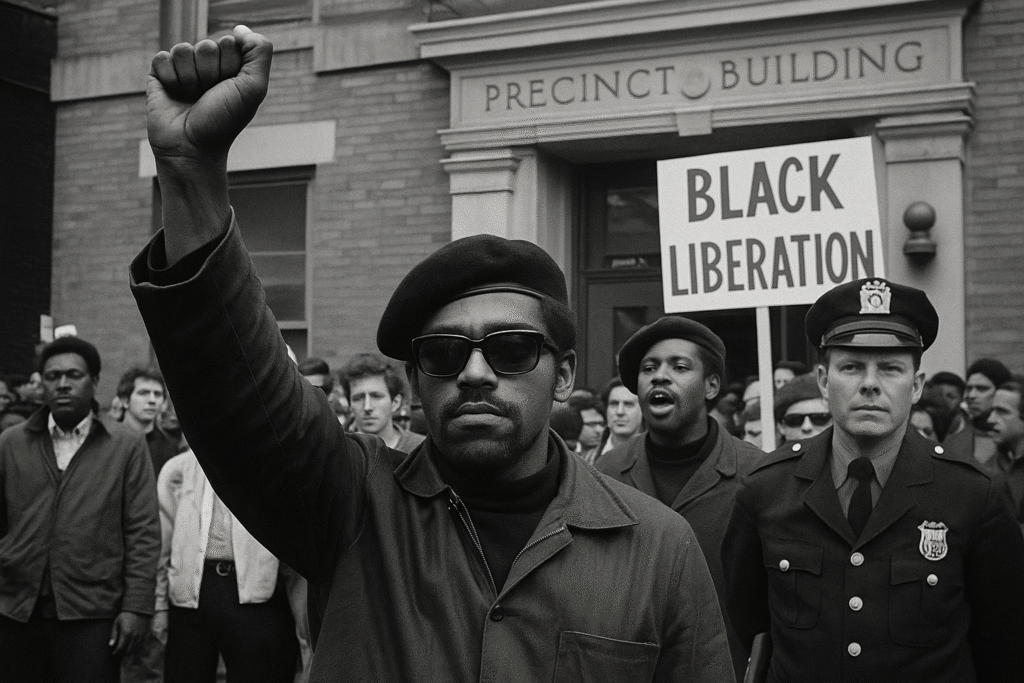

Meanwhile, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, originally founded in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, had evolved into one of the most visible—and controversial—organizations of the Black Power era. By 1969, the Panthers were operating a variety of community-based programs, including free breakfast initiatives, health clinics, and educational outreach. Yet their confrontational stance toward police brutality and capitalism drew intense scrutiny. The FBI’s COINTELPRO program specifically targeted the Panthers with infiltration, surveillance, and propaganda, aiming to sow discord and dismantle the group’s influence.

Traditional civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP, SCLC, and the increasingly radical Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), remained active, though their unity began to splinter. Tactical disagreements emerged between older leaders advocating nonviolence and a younger generation frustrated with incremental progress. These internal tensions reflected a broader shift: the movement was no longer monolithic but evolving into a coalition of voices, ideologies, and strategies—all seeking justice through their own means in a changing America.

The Shifting Dynamics: Civil Rights Movement Beyond Traditional Boundaries

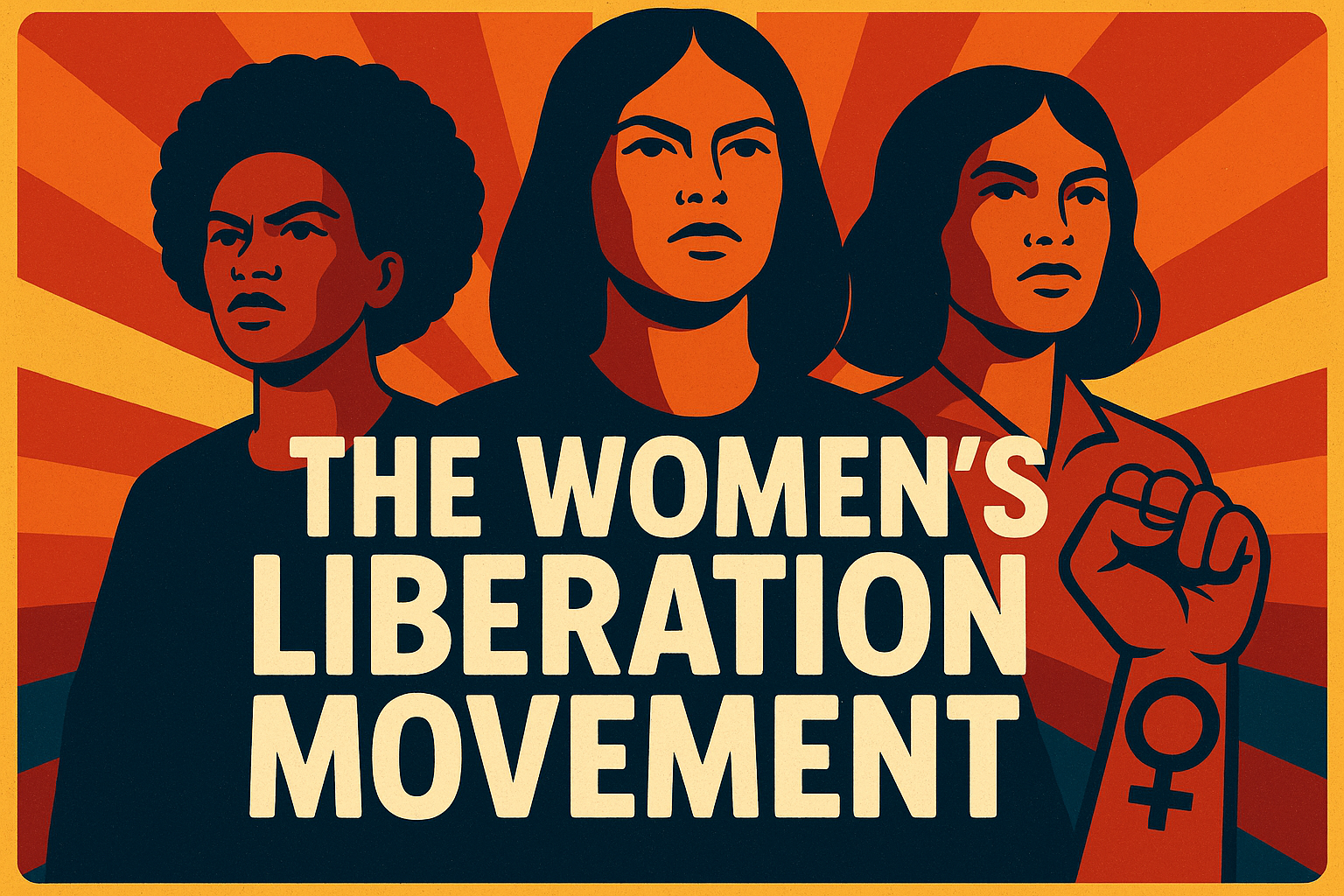

By the end of the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement was no longer a singularly focused campaign for racial equality—it had evolved into part of a broader tapestry of social justice activism that was redefining the American conscience. The events of 1969 revealed how the struggle for civil rights had become deeply interconnected with other movements challenging entrenched systems of oppression.

Foremost among these parallel struggles was the women’s rights movement, which was gaining significant traction during this period. Advocates pushed for equal pay, access to contraception, and greater representation in politics and the workplace. Importantly, many African American women stood at the crossroads of both the civil rights and feminist movements. Activists like Dorothy Height, Angela Davis, and others emphasized the importance of addressing gender and racial injustice as interlocking systems. Their dual roles highlighted the necessity of an inclusive approach to justice—one that acknowledged both race and gender as crucial dimensions of inequality.

Internationally, the reverberations of the American Civil Rights Movement could be felt far beyond U.S. borders. The language, imagery, and successes of civil rights leaders in America provided both inspiration and strategic blueprints for anti-colonial and liberation movements in countries such as South Africa, Jamaica, and Ghana. The rhetoric of equality and justice echoed across oceans, reinforcing a global awareness of shared struggles against oppression and imperialism.

Meanwhile, youth activism surged with new vigor. Students at colleges and high schools across the country organized against not only racism but also the escalating Vietnam War, censorship, and economic inequality. Many of these young voices were shaped by the counterculture movement, which rejected materialism, conformity, and traditional authority. This ethos of resistance gave rise to powerful student groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), who brought grassroots energy and idealism to both local and national protests.

At the same time, new leaders began to emerge, steering the Civil Rights Movement in fresh directions. Figures such as Jesse Jackson, who launched Operation PUSH to promote economic self-sufficiency among African Americans, and evolving organizations like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), adapted their missions to reflect the changing demands of the time. These leaders emphasized economic empowerment, voter registration, and political participation as critical next steps in the long march toward justice.

1969 thus represented a turning point—an era where civil rights activism crossed traditional boundaries, engaged with global movements, and embraced a more intersectional and expansive vision for justice. The movement was no longer only about legal rights; it had become a deeper cultural force aimed at transforming hearts, systems, and societies on multiple levels.

A Legacy Taking Shape: The Long-term Impact of 1969

The year 1969 did more than spotlight civil unrest and social division—it became a historical inflection point that shaped the future of the Civil Rights Movement and laid a foundation for progressive activism in the decades that followed. Its legacy is not confined to history books; it lives on in legislation, community programs, and the enduring spirit of resistance.

One of the most significant legislative outcomes influenced by the activism leading up to and surrounding 1969 was the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which aimed to dismantle discriminatory practices in housing. Though passed a year earlier, its enforcement and evolution remained a pressing issue in 1969. The law represented a critical attempt to equalize opportunities in home ownership and rental access for African Americans and other minorities. However, resistance at local levels—from redlining to zoning manipulation—demonstrated that legal reform alone was insufficient without robust enforcement and continued civic engagement.

Another enduring influence was the Poor People’s Campaign’s focus on economic justice. Initiated by Dr. King and carried forward after his assassination, the campaign framed poverty as a civil rights issue. Its legacy can be seen in ongoing conversations about minimum wage, access to healthcare, affordable housing, and equitable taxation—issues that remain central to today’s policy debates and progressive platforms.

Likewise, the community-based survival programs of the Black Panther Party, including free breakfast for children, health clinics, and educational outreach, helped redefine what grassroots activism could look like. Many of today’s social programs, including nonprofit food banks and community health initiatives, trace their DNA to these 1969-era efforts.

Equally impactful are the personal narratives and oral histories preserved from this period. These testimonies offer more than emotional resonance—they provide invaluable primary sources for historians, educators, and activists alike. From student protestors to neighborhood organizers, their reflections help keep the Civil Rights Movement alive as a living, breathing influence, not merely a chapter in American history.

Ultimately, the events of 1969 catalyzed a deeper and more inclusive vision of civil rights, expanding the conversation beyond desegregation to encompass housing, poverty, health, and justice. This legacy continues to guide movements for equity in the 21st century.

In conclusion, the Civil Rights Movement in 1969 was a period of significant transformation, characterized by both progress and persistent challenges. The movement’s expansion beyond traditional boundaries, its intersection with other social causes, and the emergence of new leadership all contributed to its enduring impact. The lessons learned and the foundations laid during this pivotal year continue to inform and inspire ongoing efforts toward a more just and equitable society.

📣 What Do You Think?

How do you see the legacy of the Civil Rights Movement continuing today? We’d love to hear your thoughts and personal reflections in the comments below.

📚 Want to explore more about this pivotal year? Don’t miss our in-depth review of “1969: The Year Everything Changed”—a fascinating book that connects the dots between movements, moments, and memories.