In a year synonymous with revolution, progress, and redefinition, 1969 was not only a turning point in politics and culture—but also in education. Against the backdrop of civil rights movements, scientific breakthroughs, and cultural awakenings, a cohort of visionary educators quietly transformed the future of teaching and learning. These pioneers didn’t just teach—they reimagined what education could be, laying the groundwork for inclusive, student-centered, and inquiry-driven learning environments that still influence classrooms today.

From headline-making reforms to the silent dedication of unsung heroes, the story of 1969’s influential educators is a tapestry of innovation, resilience, and belief in the transformative power of knowledge.

Pioneers of Pedagogy: Educators Who Shaped 1969

The year 1969 saw significant educational reforms, spurred by mounting societal pressure to address inequality, outdated curriculum models, and rigid classroom hierarchies. It was a year when the student voice grew louder, and progressive thinkers within the educational system rose to meet the moment.

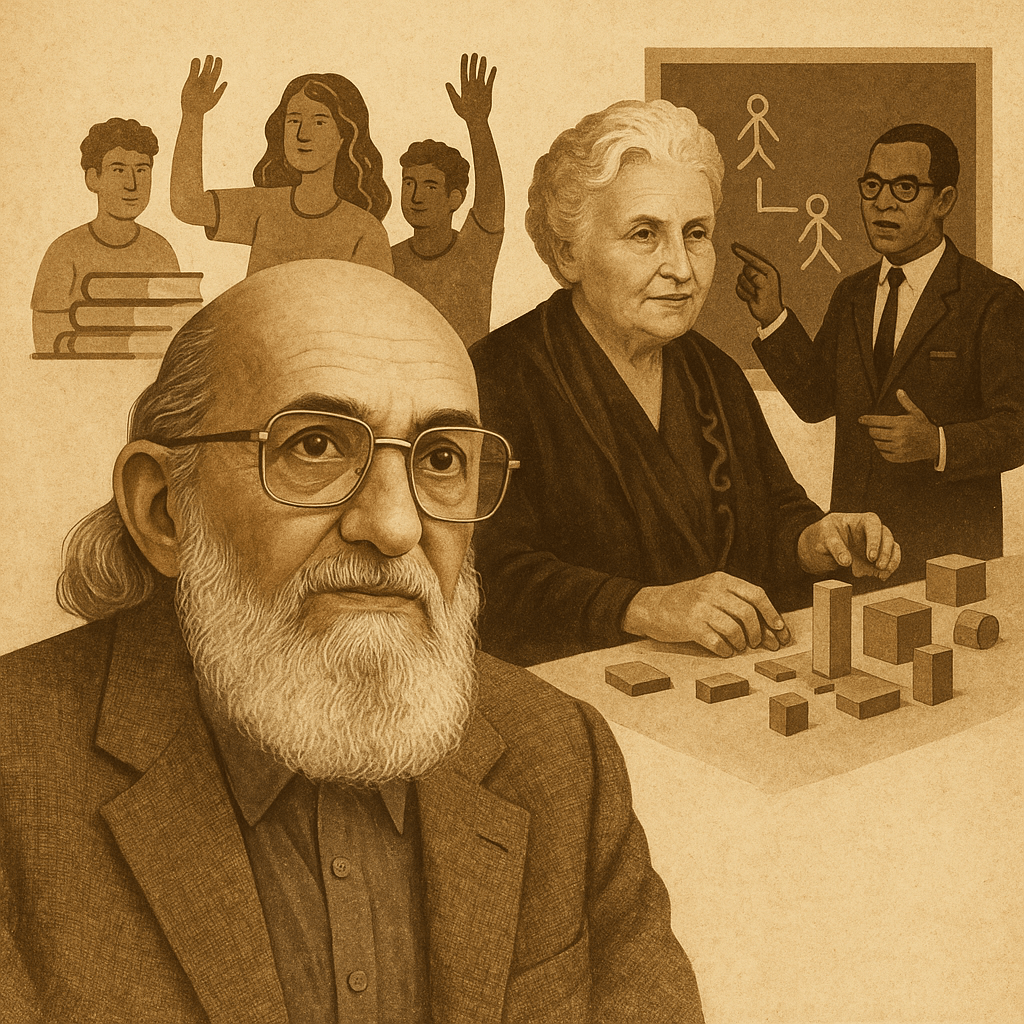

One of the most influential figures was Paulo Freire, whose landmark book Pedagogy of the Oppressed was published in English in 1969. Though written earlier, the English release brought his radical educational philosophy to a global audience. Freire emphasized dialogical learning, empowering students to question and transform their reality. His concept of the “banking model” of education—as a flawed, oppressive system—sparked international discussions on pedagogy and social justice. Freire’s legacy lives on in modern educational methods that value student agency and critical thinking.

In the United States, Dr. James P. Comer, a professor at Yale, launched the Comer School Development Program in 1969. This initiative was a groundbreaking effort to improve educational outcomes in low-income communities by focusing on the social and emotional development of children—an idea that would become standard decades later under SEL (Social Emotional Learning) frameworks. Dr. Comer believed schools should be centers of community and well-being, not just academic performance, and worked closely with parents, teachers, and mental health professionals.

Meanwhile, Maria Montessori’s educational philosophy was experiencing a resurgence in 1969, with educators adapting her ideas of self-directed, experiential learning for diverse learning environments. Montessori’s influence could be seen in early childhood classrooms across Europe and North America, where educators embraced hands-on materials, mixed-age groupings, and child-led exploration.

The educators of 1969 were deeply shaped by the societal movements of their time—civil rights, feminism, anti-war activism—and brought those values into their classrooms. They saw education as a pathway to liberation and equality, and their innovative methods and philosophies continue to inform the best of today’s pedagogy.

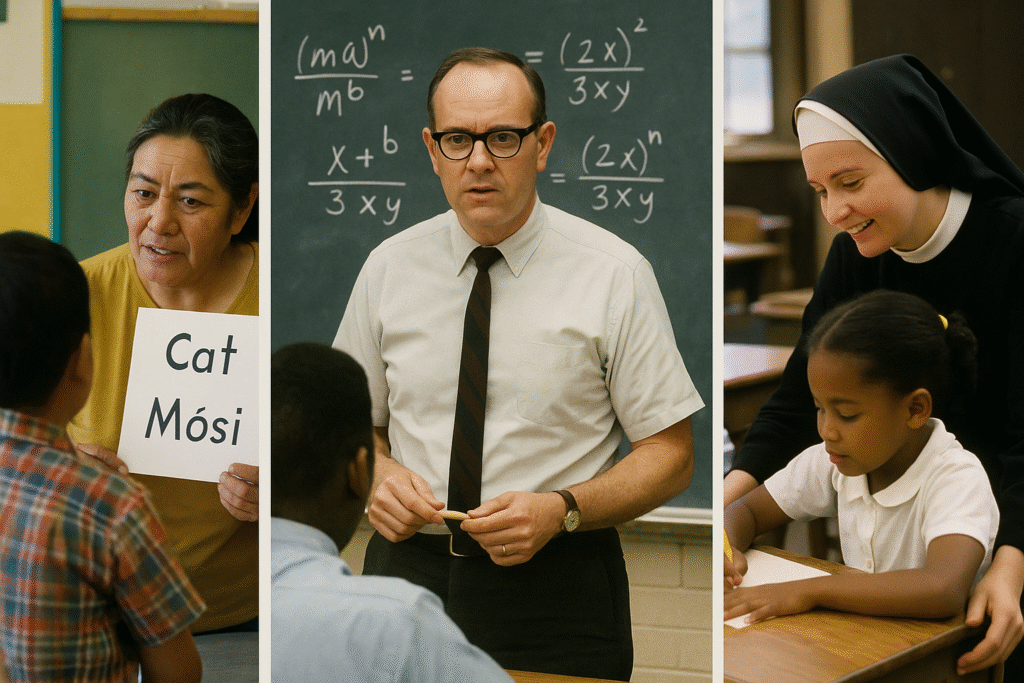

The Visionaries: Teachers Who Broke Boundaries

Beyond theorists and administrators, there were frontline teachers who defied convention to change students’ lives. These visionary educators took risks in their classrooms, using bold strategies to enhance learning outcomes and engage young minds in unprecedented ways.

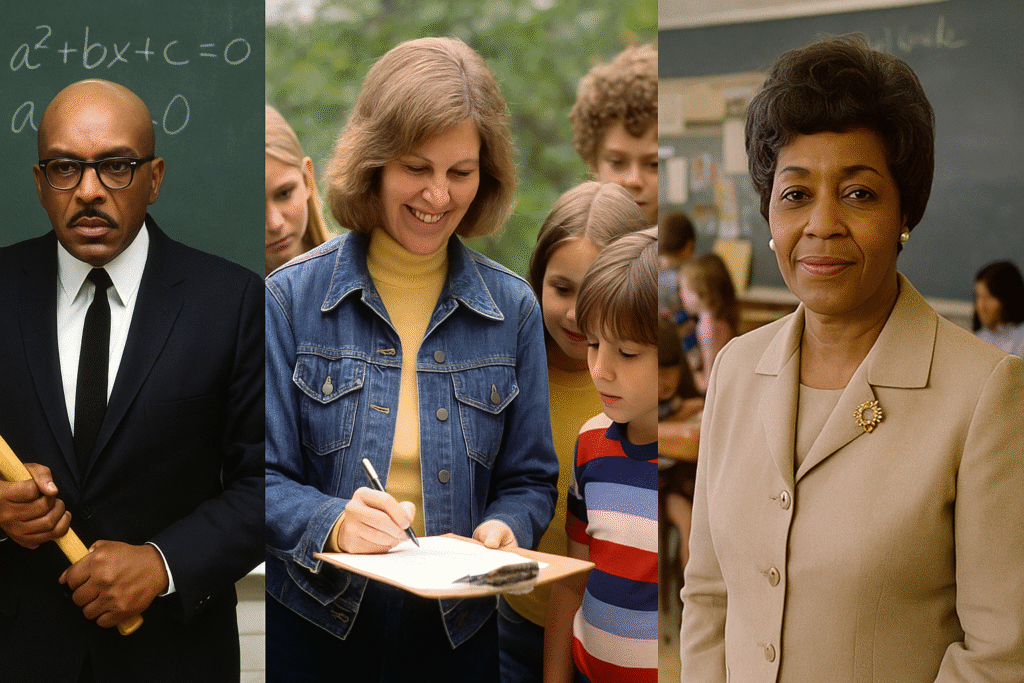

One such figure was Joe Clark, an uncompromising principal and educator in New Jersey, whose approach to discipline and academic rigor in struggling schools became legendary. Though most of his notoriety came in the 1980s, his early work in the late ’60s laid the foundation for his philosophy of high expectations, accountability, and empowerment. His life was later dramatized in the film Lean on Me, but his commitment to rebuilding failing schools began in 1969.

In rural and urban schools alike, teachers began to embrace project-based learning—a concept that emphasized real-world problem solving, teamwork, and inquiry. Ruth Feldman, a science teacher in San Francisco, introduced community ecology projects that connected students with environmental causes—an idea sparked by the first Earth Day organizing efforts that began in late 1969. Her students’ water testing and pollution mitigation efforts predated many modern environmental science programs.

Another trailblazer was Elizabeth Koontz, appointed in 1969 as the first Black woman to lead the National Education Association (NEA). Though not a classroom teacher in that moment, her platform advocated for racial equity in school hiring, curriculum reform, and funding allocation. Koontz was instrumental in raising awareness about systemic inequalities and in pushing for bilingual and multicultural education reforms.

Classroom practices were evolving rapidly. Open classroom models gained traction in 1969, especially in experimental schools across the U.S. and U.K. These models abandoned rigid desks and teacher lectures in favor of learning centers, flexible grouping, and thematic units. A study conducted in 1970 by the U.S. Office of Education showed that schools piloting open learning environments in 1969 experienced increased student engagement, creativity, and collaboration, especially among underserved populations.

Students taught by these educators often recall transformative experiences: “I used to hate school until Ms. Feldman taught us that science was about asking questions,” shared one former student in a 2020 interview. “She taught us to see learning everywhere—in the soil, in the trees, in our curiosity.”

Unsung Heroes: Acknowledging the Lesser-Known Influencers

While some educators of 1969 made headlines, many made history quietly, changing lives in classrooms that never saw the spotlight. These unsung heroes brought innovation, compassion, and rigor to their work, often under challenging circumstances.

Robert “Bob” Wetherall, a math teacher in Birmingham, Alabama, introduced peer tutoring and differentiated instruction in his segregated high school classroom in 1969. Despite limited resources, he fostered an environment of academic excellence and peer support. “We didn’t have calculators or new books,” one of his former students recalls, “but Mr. Wetherall made us feel like we had the tools to solve anything.”

In the Navajo Nation, Helen Tsosie pioneered bilingual education, integrating English and Navajo in early reading programs—an effort not widely supported by state authorities at the time. Her insistence on cultural preservation and language integration allowed students to thrive academically while honoring their heritage.

Sister Bernadette McKenna, a Catholic school teacher in New York, revolutionized religious education by incorporating social justice and community service into her lessons. Long before “service learning” became a buzzword, Sister Bernadette took her students to local shelters and soup kitchens, turning abstract moral lessons into concrete action. Her methods were controversial at first, but years later, her former students credited her with awakening their lifelong commitment to civic engagement.

Many of these educators worked in underfunded, marginalized communities, facing institutional resistance, racial discrimination, or bureaucratic inertia. Yet they persevered—because for them, teaching wasn’t a job; it was a calling.

Their stories, often documented in oral histories, local archives, and retrospective testimonials, paint a rich portrait of commitment and innovation at the grassroots level. In many ways, these educators were the foundation of future reform movements, embodying values and methods that would only later be recognized as groundbreaking.

Legacy and Influence: How 1969 Educators Shaped Modern Education

The long-term influence of 1969’s educators is woven into the fabric of today’s educational systems. Many of the concepts they pioneered—student-centered learning, cultural inclusivity, project-based instruction, social-emotional education—are now considered best practices in schools around the world.

Paulo Freire’s ideas about dialogical learning have been integrated into literacy programs and liberation education frameworks globally. His influence is evident in organizations like Teaching for Change and The Zinn Education Project, which emphasize critical pedagogy and student empowerment.

Dr. James Comer’s whole child approach has become a cornerstone of modern educational psychology. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) cites Comer’s model as a key precursor to today’s SEL movement, which is now implemented in over 30% of U.S. school districts.

Educators from 1969 helped to democratize the classroom, replacing authoritarian models with collaborative, student-driven environments. Open classrooms, interdisciplinary learning, and culturally relevant teaching—concepts once considered radical—are now being scaled globally through initiatives like International Baccalaureate (IB) and Montessori education.

Many of these legacies are preserved through books, interviews, and academic studies. Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed remains required reading in teacher training programs. Koontz’s legacy is honored through scholarships supporting minority educators. Oral history projects from the Library of Congress and various university archives continue to collect and share the testimonies of teachers from this transformative era.

For those looking to explore the influence of 1969’s educators, recommended readings include:

- Pedagogy of Hope by Paulo Freire

- Child by Child by Dr. James Comer

- Savage Inequalities by Jonathan Kozol (highlighting the lasting systemic issues educators like Koontz sought to address)

- The Freedom Writers Diary by Erin Gruwell and her students (a modern echo of 1969’s educational rebellion)

Today’s challenges—digital learning, mental health crises, educational inequality—require solutions that echo the wisdom of the past. The bold, student-centered ethos of 1969’s educators offers a blueprint for teaching that is not only effective but transformative.

Conclusion: Teaching the Future by Remembering the Past

The influential educators of 1969 did more than teach—they challenged, inspired, and reimagined what education could be. Through innovation, advocacy, and resilience, they transformed classrooms into catalysts for change and set the stage for generations of learners to thrive.

As we continue to face complex global and educational challenges, the voices of 1969 remind us that education is not static—it is a living force, shaped by those brave enough to think differently, speak out, and care deeply. The legacies they left behind are not merely historical—they are active ingredients in the classrooms, philosophies, and breakthroughs of today.

📘 Dive Deeper into 1969

Want to explore more about the transformative events that shaped a generation? Check out our review of 1969 – The Year Everything Changed by Rob Kirkpatrick.

Read the Book Review